Giving it a Shot: Finding a balance between the Student and the Athlete

- Kinsie Huggins

- Nov 11, 2022

- 5 min read

From the age of three I’ve wanted to be a doctor, a pediatrician specifically. The community I lived in didn’t have many doctors that resembled me. Therefore, my mom made the effort to find an African-American doctor, who became my role model for most of my life. This strengthened my ambition to diversify the medical field and led me to prioritize this goal throughout my education.

When I was 10, I started track and field. I was fascinated by the multiplicity of events I could participate in. I stuck with it because I enjoyed pushing myself to my physical limits as an escape from pushing myself to my academic limits. I visited Duke while I was in North Carolina for a track meet, and I saw ample opportunity to set myself up as a successful doctor. I applied, thinking Duke was my reach school and getting in was a long shot; however, I beat the odds and was accepted.

At this point, I was ready to give up track and field. I hadn’t been recruited by Duke, and I knew that I had a long way to go to be competitive in the ACC. Despite knowing that adding the pressure of D1 athletics on top of my goals would be challenging, I decided to reach out to the coach by email. He saw my potential and gave me the opportunity to walk onto the team.

"As an athlete, I didn’t have as much autonomy as I thought I would. "

I got to Duke and was amazed by everything I could be involved in. There were people from all walks of life. The East Campus quad was covered in tables showcasing organizations and clubs to join. There were classes on every subject imaginable, and I wanted to take all of them. The reason I chose to come to Duke was because of all the spaces I could put myself in to aid others and develop the characteristics I needed to become a medical professional. Little did I know, that wouldn’t be possible. As an athlete, I didn’t have as much autonomy as I thought I would.

“That class conflicts with your practice schedule; take this one because it fulfills the same requirement,” an advisor told me. I’d shrug my shoulders and do as they said, unconsciously learning to only take classes that fit requirements rather than ones that look the most interesting.

“Hey let’s take this lab together, we can be lab partners and complete experiments together." I had to reply that I couldn’t because I couldn’t make labs on Thursday or Friday during track season. I found myself working through concepts independently, and being too anxious to ask for help.

“Do you understand this homework problem? I’m going to go to office hours to ask the professor for help if you want to come with." Again, I had to say no because I had practice or lift. I built a false conception in my mind that professors perceived me as lazy, when in reality I just didn’t feel comfortable saying the only time I was free to meet was after 5pm Monday through Wednesday.

Outside of classes, I found extracurriculars that were flexible with my track schedule. I joined CoachtoInspire where I got to mentor kids in Durham and coach basketball, which was often the highlight of my week. I joined two research teams, one studying the Sickle Cell Trait Testing Policy in the NCAA where I got to interview athletes nationwide, as well as a Genomics of Kidney Disease Lab. I was a mentor for BioStems, an organization for mentorship of high school students in STEM. I was a contact tracer during the pandemic. I even joined United Black Athletes and spoke on panels to bring awareness to biases in college sports and minority athlete experiences. I looked forward to participating in these organizations during the week because they aligned with my ambition to diversify the medical field and be a mentor to individuals younger than me. As my purpose and passion grew through participation in extracurriculars, I could sense my excitement and motivation for track and field diminishing. It started to worry me because out of all my extracurriculars, my sport, being the one that took the most time and effort, was the one I dreaded the most.

"I started to think being a Division I athlete wasn’t worth it, that it wasn’t worth having as an extracurricular. And there lies the problem. For the first time in my life, my sport was not an extracurricular."

Sophomore year I threw the 3rd best outdoor mark, and Junior year I threw the 4th best indoor mark for shot put in Duke history. Despite the success, I resented my sport. Once pre-med courses started to get harder, during practice I would think about how I could be doing homework or attending office hours instead. I’d feel bitterness towards my friends because they had ample time during the day and on the weekend to study for tests, whereas I couldn’t start studying until 6pm at night on a bus (without wifi) to Virginia, or at a track meet with my body sprawled across a bench or the floor.

"I refused to acknowledge the complexity of being a Division I Athlete and the entanglement between my identity and track and field."

I was a walk-on athlete. I didn’t receive any scholarship to participate in track & field. How was this benefiting me in my mission to become a doctor? It felt like it wasn’t. I started to think being a Division I athlete wasn’t worth it, that it wasn’t worth having as an extracurricular. And there lies the problem. For the first time in my life, my sport was not an extracurricular. Track and field was my second major. I tried so hard to keep my sport from becoming my identity, but rather something that I did for fun. I refused to acknowledge the complexity of being a Division I Athlete and the entanglement between my identity and track and field.

"I contemplated separating my identity from athletics completely. Instead, I’ve made being a pre-med student athlete a strength, not a weakness. "

I’ve met many mentors at Duke, two of the most impactful being Dr. Rasheed Gbadegesin, who I do nephrology research under, and Dr. Robert Thompson, who has seen me evolve from being a freshman in his Empathy/Identity Psychology Seminar to a Senior at Duke preparing to graduate and apply to med school. Both of them have repeatedly reaffirmed to me that being an athlete COMBINED with all of the organizations and spheres I have been a part of contribute, rather than take away from, who I am. I am grateful that the determination, persistence, diligence, versatility, and productivity I have gained from participating in athletics will allow me to prosper in my passion for the health of others.

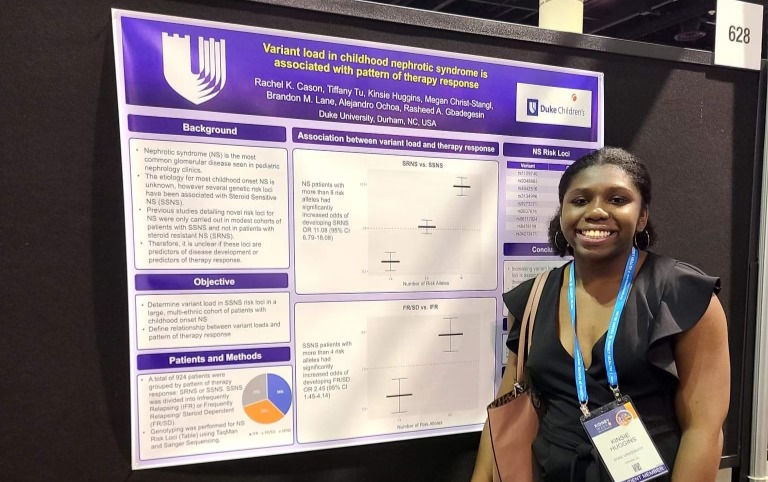

I was often mistaken for only being at Duke because I was an athlete. I contemplated separating my identity from athletics completely. Instead, I’ve made being a pre-med student athlete a strength, not a weakness. After all, it’s Friday Nov. 4th and I’m here writing this at The American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week National Conference where I’ll be giving a platform presentation on research I helped conduct, something I never thought I’d be able to accomplish as an undergraduate! And then I’ll fly back to Durham and practice like a normal athlete on Monday. This is the life I chose, and I’m choosing to embrace it.

I challenge you to explore all of your interests plus some, and seek wisdom from mentors who encourage you to embrace all of the aspects of your identity. As complex, messy and uncertain as you may think your identity is, acknowledge the strength it provides you and use it to propel you forward in accomplishing your dreams.

- Kinsie Huggins

Photo Credits: Duke Athletics and Kinsie Huggins

Comments